Psychosis, clinically defined, is a loss of contact with reality—where perception, thought, and belief no longer align with what’s actually happening. Hallucinations feel real. Delusions feel certain. The mind becomes convinced of stories that cannot be questioned.

Clinically, this is serious and deserves care, compassion, and professional support.

But there’s another way to use the word psychosis—not as a diagnosis, but as a description of a structure.

Because if psychosis means mistaking internal narratives for reality itself, then something uncomfortable becomes visible:

Our ordinary sense of self operates this way almost all the time.

This Is Not About Mental Illness

This article is not claiming that mental health conditions are simply exaggerated versions of normal thinking.

OCD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and related diagnoses involve real suffering, neurobiological factors, and complex personal histories.

What this article points to is something more fundamental:

The mechanism that becomes visible in psychological disorders

is the same mechanism quietly organizing everyday identity.

The difference is not kind.

It’s intensity, rigidity, and awareness.

The Self as a Functional Delusion

Most people experience themselves as a stable, continuous “someone.”

A character with:

- a past

- a personality

- preferences

- wounds

- intentions

- a future to manage

That character feels obvious.

But notice something subtle:

You never directly experience a self.

You experience:

- thoughts about yourself

- memories describing yourself

- images of who you think you are

- stories explaining why you feel what you feel

And then something crucial happens:

You believe those descriptions are what you are.

That belief is rarely questioned.

Because it works.

Why It Doesn’t Look Like Psychosis

In clinical psychosis, beliefs are idiosyncratic and isolating.

In everyday identity, the belief is shared.

We all agree that:

- there is a thinker behind thoughts

- a chooser behind choices

- a doer behind actions

- a someone who owns experience

Because everyone agrees, the belief becomes invisible.

But consensus does not equal reality.

It only equals normalization.

This is the quiet engine behind what we explore more broadly in the self you’re trying to hold together.

When the Narrative Tightens

Psychological distress often arises when the self-narrative:

- loops compulsively

- contradicts itself

- becomes grandiose or fragile

- stops updating with new information

- or becomes emotionally uninhabitable

Obsessions.

Ruminations.

Identity collapse.

Inflation.

Paranoia.

What we call “disorder” doesn’t introduce a new structure.

It exposes the structure that was already there.

Identity as a Map Mistaken for Territory

The self is not useless.

It’s a map.

It organizes memory, coordinates behavior, and allows social interaction.

But a map mistaken for territory becomes dangerous.

When identity is taken literally:

- thought feels authoritative

- emotion feels definitive

- memory feels factual

- prediction feels certain

And suffering follows—not because anything is “wrong,” but because flexibility is lost.

The Shared Agreement That Keeps It Hidden

Imagine if everyone around you believed the same hallucination.

Not visually.

Not auditorily.

Conceptually.

You would never question it.

You’d build:

- cultures

- economies

- moral systems

- religions

- psychologies

Around it.

That’s exactly what’s happened with the belief in a separate, continuous self.

Because it’s ubiquitous, it’s rarely examined.

Why This Isn’t a Condemnation

Calling this a collective psychosis is not meant to shame or pathologize humanity.

It’s meant to normalize something important:

Relief often comes when the self-story loosens.

When thoughts are seen as thoughts.

When identity is seen as narrative.

When “me” is seen as a useful fiction rather than an entity.

Nothing needs to be destroyed.

Nothing needs to be believed.

Nothing needs to be replaced.

Only noticed.

Breakdown vs. Insight

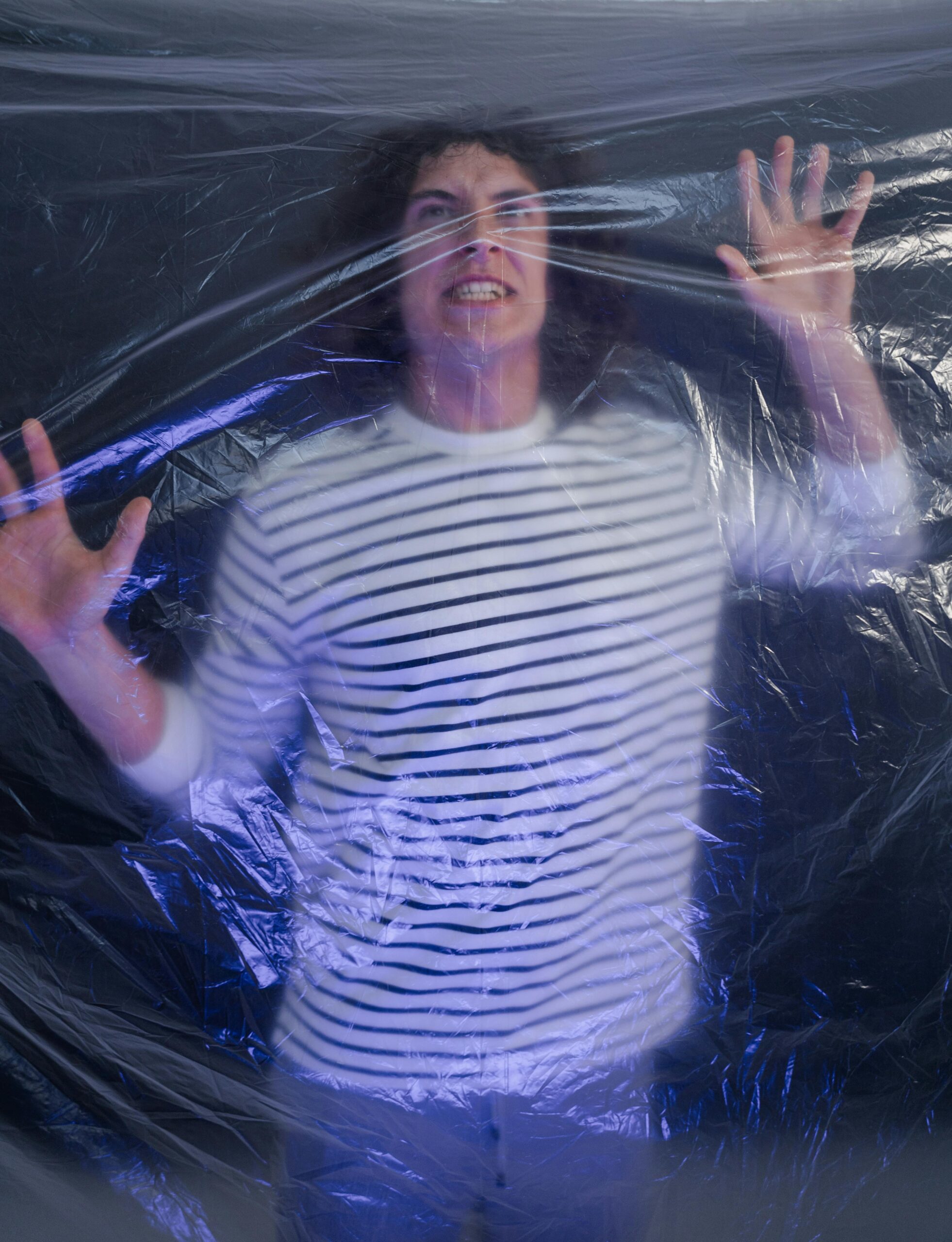

When this structure collapses unintentionally, it can feel terrifying.

When it’s questioned gently, it can feel liberating.

The difference isn’t intelligence.

It’s context, support, and interpretation.

One feels like losing reality.

The other feels like finally touching it.

Why This Matters Culturally

We live in a time of escalating certainty and identity fixation.

People are more convinced than ever.

And more anxious than ever.

That’s not accidental.

The tighter the narrative of “me,” the more fragile it becomes.

And fragility seeks certainty.

The Invitation

Proof That You’re God doesn’t claim the self is evil, broken, or unreal.

It points to something quieter:

What we call “normal” is simply a shared misunderstanding

that works well enough to function—

until it doesn’t.

Seeing that isn’t madness.

It’s the beginning of sanity.

Not as a new identity.

Not as a diagnosis.

But as a loosening.

The moment the story is no longer mistaken for what’s real.